January 2018

WHITINSVILLE - Photographing abandoned asylums, Mike and Joanne Zeis evoke the forgotten lives of people who once lived in institutions now ruined and closed to the public.

Like archaeologists with cameras, the husband-and-wife photographers from Uxbridge explore the detritus of earlier times to recover in striking images a nearly vanished culture of troubled people and those who cared for them.

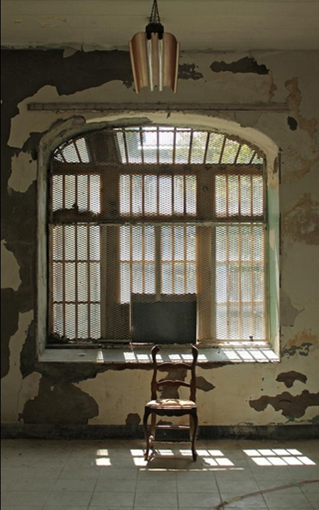

Titled “Bringing Light to the Darkness,” the 40 photographs displayed at Alternatives Unlimited’s Aldrich Heritage Gallery in Whitinsville discover beauty in decaying ruins and the poignancy of lives confined to now-outdated institutions.

By conjuring images of the grim, institutionalized settings, they cast a revealing light on how the mentally ill were treated in the past while suggesting the need to integrate them into a more welcoming environment today, said Cristi Collari, director of community outreach at Alternatives.

The Zeises are among a handful of photographers who enter abandoned properties such as mental health institutions or factories - sometime without permission - in search of memorable images.

A photographer since childhood, Mike Zeis finds tales of sorrow and hope in once-grand buildings now wasting away from time and neglect.

A faded yellow sign decorated like old needlework welcomes inmates to Ward E. Once-colorful clothes spill out of two mildewed suitcases. A row of half-opened doors to rooms where people once lived protrude into a darkened hallway.

“I’m fascinated by the way time affects the objects we build. Textures change. I have to work with the odd bits of light,” said Zeis, a former market researcher who began taking pictures 50 years ago when his parents gave him a Kodak Brownie camera. “I hope my photos help viewers imagine what it must have been like to live and work there.”

Zeis declined to identify where the photographs were taken except to say they were in New England.

A painter, musician and writer of medical texts, Joanne Zeis aims to capture through her photos how the subtle play of limited light elicits the long-ago experiences of staff and patients.

Scraps of delicately-woven lace are draped over an old, dirty bathtub. A row of green shuttered windows prevents sunlight from brightening a long, drab corridor. Covered by weeds, a rusted slide stands empty outside a building.

The photos are for sale.

The Zeises were invited to show their work at Alternatives Unlimited after Dennis H. Rice, cofounder and executive director of the nonprofit, saw and purchased some of the now displayed photos at another venue.

Collari, who supervises the gallery and organized the exhibit, said it also includes artifacts from the Museum of disABILITY History and New York State Museum, such as leather belts with cuff-restraints used to restrict patients’ movements.

She arranged photos in ways she hoped would show visitors “the tragedy” of isolating and “warehousing behind closed doors” disabled people in impersonal institutions.

By showcasing the errors of the past, Collari said, the exhibit reflects Alternative Unlimited’s mission of “creating a community life where people with psychiatric and developmental issues can thrive and not just survive.”

“We’re interested in raising awareness of how people were treated in the past and how far we’ve come,” she said.

Since many institutions that once treated the mentally ill have been closed to the public, he promotes an “explorers’ ethic” that urges photographers to enter through existing openings in fences or walls but not to break in or damage or disrupt the sites.

While many asylums were designed along principles espoused by Thomas Kirkbride, a 19th-century advocate for the mentally ill, to maximize light and air, Marsala said neglect and vandalism “caused many good institutions to become hellholes.”

Photographers of abandoned sites often must bring their own lighting sources and even respirator masks to protect them from mold, lead and asbestos, he said.

“I think there is inherent beauty in how nature takes over,” said Marsala. “We have to show respect for not only the building but also for the people who called these places home, all those who lived and died there.”

The photos of Mike and Joanne Zeis bring alive those forgotten people in images of poignant beauty.

An empty chair sits before barred windows. Without stalls for privacy, four toilets extend from a wall. A cheap, metallic Christmas tree topped with a green star sits atop a windowsill.

“We look and get a better understanding of what used to be,” said Mike Zeis. “What persists is the need for our systems to provide care for those who have difficulty caring for themselves.”